In school and public libraries across the country, efforts to ban books are on the rise.

For Christi Bukar, executive director of the Pennsylvania Library Association, a statewide chapter of the American Library Association (ALA), these bans are contrary to a library’s mission, as outlined in the Library Bill of Rights.

“Part of what we do in our association, as well as in other statewide chapters, is work to make sure that residents across the nation have free and unfettered access to information regardless of your personal viewpoint and without restricting access to others,” Bukar said.

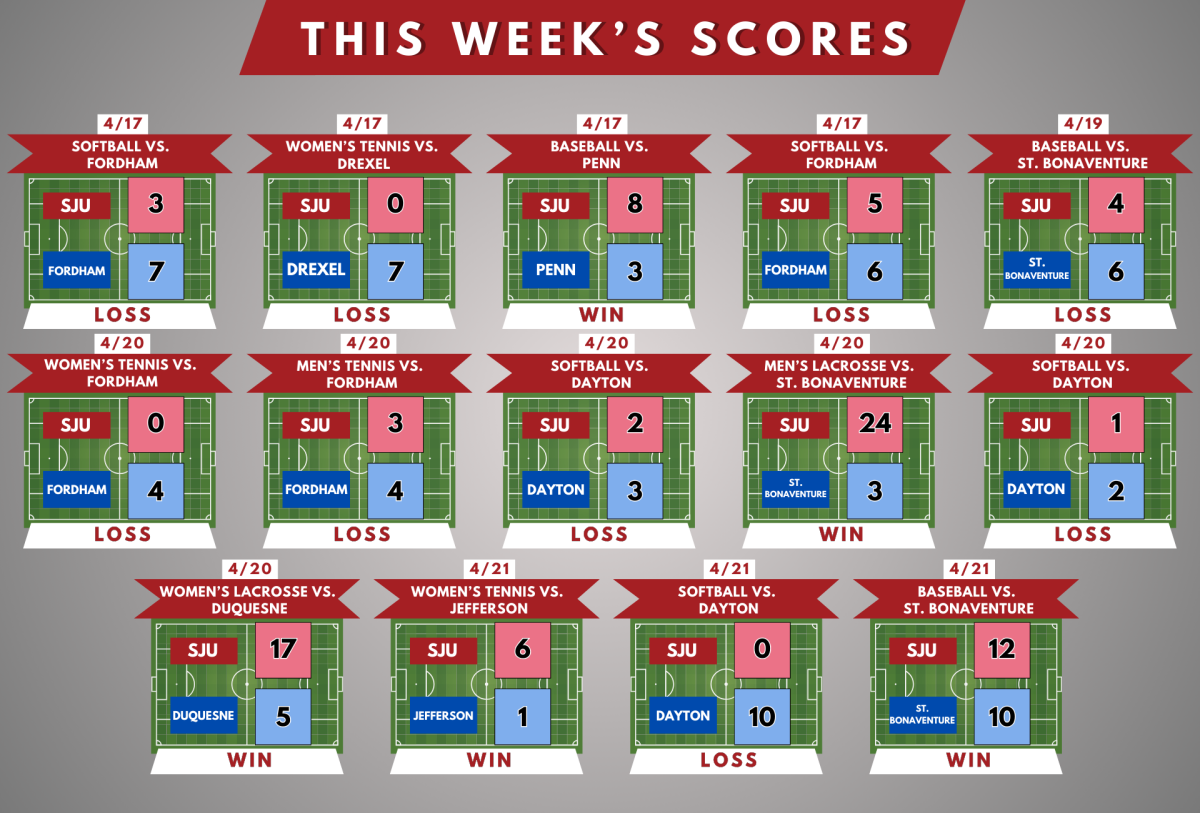

The ALA saw more challenges to books in 2021 than they did in the previous two decades. Last year, there were 729 challenges on books at libraries and universities across the country, marking a 90% increase from the 377 challenges the ALA saw only two years earlier in 2019.

As of 2021, the top five most challenged books as tracked by the ALA are “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison, “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson, “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Peréz and “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas. These books are banned for LGBTQ+ content, depictions of abuse, sexually explicit content, profanity and violence, which challengers say is linked to an anti-police message.

Providing library patrons with access to books like these has become more challenging due to organized groups of people visiting individual local libraries with a script of why a book is objectionable, Bukar said.

“Unfortunately, we are seeing a lot of strong political movements and organizations that represent specific points of view and organize efforts [to remove books from libraries],” Bukar said. “That has certainly contributed to the increase [in banned books]. In the past, a lot of challenges and book bans came from an individual who was in the library and happened to come across something that they objected to and then they would file a challenge.”

Pennsylvania is second in the nation, behind Texas, in book challenges and bans, according to PEN America data.

In the Philadelphia area, the Central Bucks School Board passed a controversial policy in July that gives a yet-to-be-determined group the power to pull books from school libraries that the group deems inappropriate, as well as allows community members to challenge books they wish to be removed.

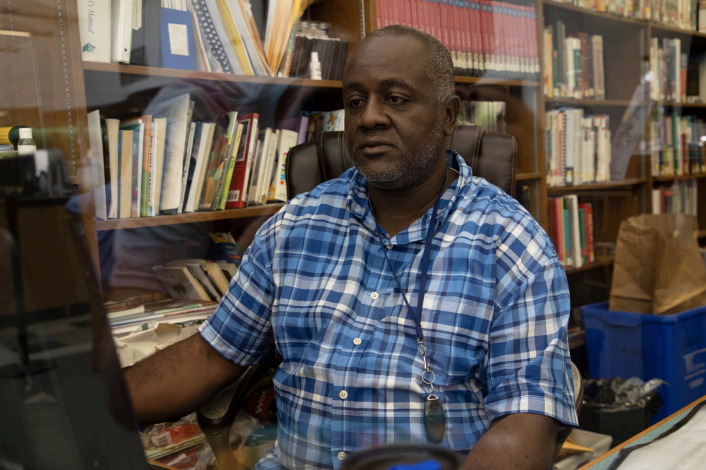

Elsewhere in the state, Nichole Owens, the librarian at Hempfield Area High School in Greensburg, located in Westmoreland County in western Pennsylvania, said the 2021-22 school year was the first time she has ever had to deal with books being challenged in the 16 years that she has been employed in the district.

A parent approached the high school librarian with five books that she wanted to be removed from the shelves, Owens said, but eventually decided to only challenge two: “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by LGBTQ activist and journalist Johnson and “The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person” by Frederick Joseph.

“All Boys Aren’t Blue” is a nonfiction memoir that explores Johnson’s adolescence as a queer, Black boy growing up in Virginia. “The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person” is written by a Black man from the perspective of a friend and is a book that was written for white people who are committed to being anti-racist.

At Hempfield Area High School, when a book is challenged by a parent or guardian, it goes through a committee – consisting of the librarian, several administrators, a teacher from the subject area that the book is in, at least two parents and at least one student – to see if “it merits staying on the shelf or if it should be taken off the shelf,” Owens said.

In this case, the committee decided that both books should remain. But after this month’s long process concluded, the parent was dissatisfied with the committee’s decision, Owens said.

“The parent decided to continue with going to the school board because they didn’t think the process was fair, because they didn’t like the decision that we came to,” Owens said. “Technically, according to the policy that is in place now, there is no further process. The books are on the shelf. They stay.”

Living in an area that does not offer much diversity creates a limited point of view, which is why sheltering students from different perspectives will only hurt them in the long run, Owens said.

The Hempfield Area School District is 92.4% white, according to the most recent U.S. News & World Report education data.

“The role of these books is to expose you to other points of view and other experiences because your world might not be so big, but the world out there is so much bigger, so you have to see other perspectives,” Owens said. “I think our kids are much more mature than people give them credit for.”

Liv, a 20-year-old Indiana University of Pennsylvania sophomore, who works at a public library in a town in western Pennsylvania, but asked that their last name not be used, said much of the blame for the increase in banned books can be attributed to an unstable political climate that “suddenly became really volatile over time.”

“The public library’s mission is to provide truthful information to the best of our ability and up-to-date information,” Liv said. “We can’t say we’re a liberal institution. We can’t say we’re a conservative institution. We’re not. We’re very in the middle. We want to cater to everyone.”

The problem, Liv said, is that banning books from libraries silences discussions and productive conversations that books can generate.

“We’re fighting for [banned books] to be out there so that we can have good discussions about it,” Liv said.

This past summer, the SJU Writing Center hosted its annual Summer Diversity Book Club with the theme of banned books. Funded by the University Student Senate and open to anyone at the university who wanted to participate, the club read three frequently banned books over the course of the summer and held a discussion about each one over Zoom. In June, participants read Kobabe’s “Gender Queer,” currently the most banned book in the U.S.

Alex Given ’24, the president of SJUPride and a participant of the “Gender Queer” book club discussion, said books like “Gender Queer” help readers find a reality that is “more akin to people who have these experiences.”

“I’m trans, and even I didn’t understand some parts of [“Gender Queer”],” Given said. “It was a really good experience to read that and in some instances, helped affirm my own identities. But I think it’s important for anyone, no matter their stage of identity or where they stand in life, to read stuff like this.”

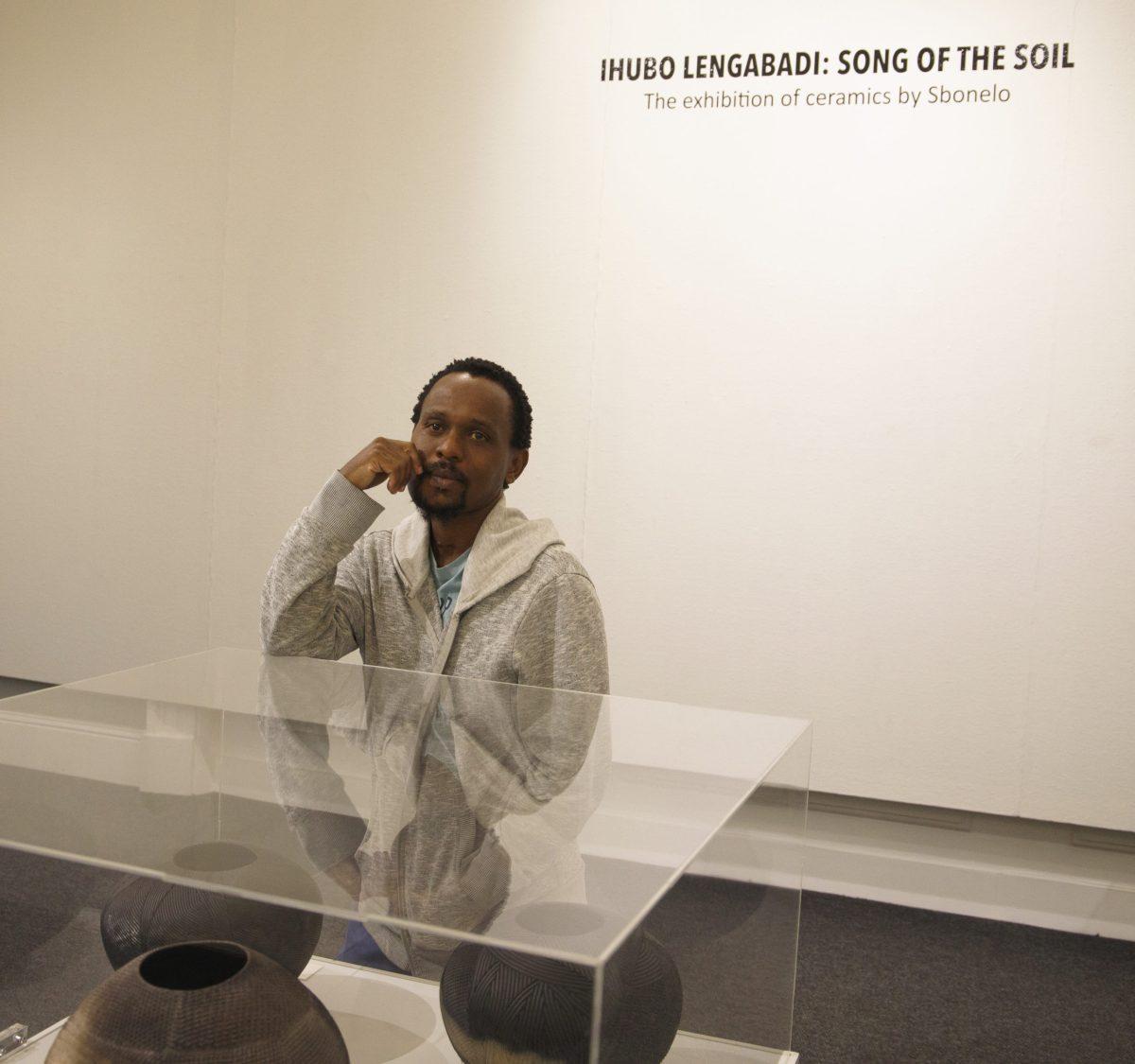

Marvin DeBose, the branch manager and adult teen librarian of the Haverford Library, a branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia, said banned books are often read in book clubs like the one the SJU Writing Center hosted. DeBose himself participates in a national book committee called “In The Margins” which puts together a list of fiction and nonfiction books for “kids in the margins.” The books cover topics like teen pregnancy, gangs and juvenile incarceration.

DeBose said he thinks the book ban could set the country back more than 50 years, not to mention the harm such bans do to people individually.

“What you’re trying to do is limit people’s creative thought pattern by telling them what they can read and what they can’t read,” DeBose said. “It’s political, to direct the thought pattern, to want people to think in one direction.”

Owens, who stressed that libraries are democratic institutions, also said book bans are about control.

“My library in particular, I find it a very comfortable space,” Owens said. “And I’ve had kids tell me that they feel very comfortable there because they can just be themselves. The people who are challenging the books, their children haven’t stepped foot in the library. So you’re taking stuff away from the kids who are actually reading the books because of your kid who isn’t in the library?”

St. Joe’s Drexel Library has three of the top five most banned books in the country on its shelves, excluding Peréz’s “Out of Darkness,” which is available as an e-book, and Evison’s “Lawn Boy.” All of the books are available through Interlibrary Loan.